Choosing a side: Understanding your own health diagnosis beyond the mental-physical divide

This is a piece dedicated to the disabled and to the chronically unwell, but specifically, to those of us who are still figuring it out. To those who mutter a working diagnosis under their breath when questioned, only to retract such a diagnosis after a second (or third, or fourth) doctor says differently. To those who are assured their symptoms are solely related to their mental health, for them to suddenly be diagnosed with a physical health condition (surprise: you weren’t imagining it!!). To those who feel guilt, who are made to feel hysterical, or those that are simply uncomfortable with their diagnosis - this is for us. Piece by Seren Oakley, 2022

Seren has depicted an episode of mine I remember vividly from my first semester at Uni. I was waiting in line to order a hot drink at a cafe near campus, when I suddenly floated above my body. I remember looking down at myself and counting the number of people in front of me before I had to order - feeling stressed I wouldn’t be able to speak to the person behind the till and simultaneously paralysed with inaction.

There has been a significant shift in societal understanding in relation to mental and physical health in the last 5 to 10 years. We now know how mental and physical health are linked - a finding relentlessly peddled by most public health services in the UK. Whilst this message may be clear, there are other assumptions made about physical and mental health which still entrench a binary logic; i.e the perception that you can only be physically OR mentally unwell and that there is no crossover between such conditions. In other words - you have to choose a side.

This piece explores the way in which people with health conditions often have to tiptoe between mental and physical frameworks of diagnosis. As an individual who had a working diagnosis of dissociative disorder (considered a mental health condition) corrected to epilepsy (considered a physical condition), I reached out to other people that have experienced this disorientating process. I was extremely grateful to discuss this topic with another young woman, Vicky, who had an epileptic condition re-diagnosed as dissociative in nature - our experiences are both paralleled and inverted. It left me thinking - do other ‘ill’ people that have switched between the binary of physical and mental feel a sense of loss as their diagnosis is retracted? Why can the experience of re-diagnosis be so validating for some people, but so invalidating for others? And what impact can this have on how we view our own health?

Before I continue, I have listed below NHS links to the health conditions mentioned within this piece, as well as other charities/websites I have found useful:

On dissociative disorders:

https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/dissociative-disorders/

Click here for a beautiful visualisation of dissociative disorder by artist Jodie Howard: https://www.jodiehoward.co.uk/unreal

On narcolepsy:

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/narcolepsy/

https://www.narcolepsy.org.uk/

On epilepsy:

On misdiagnosis and Functional Neurological Disorders:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/ideas/videos/the-misdiagnosis-that-sent-me-to-psychiatric-hospi/p0dqf3km

My journey to a *hesitant* diagnosis of a dissociative disorder

I first began questioning my health as a student at University, where I experienced disorientating episodes that left me wondering what was reality and what was in my head. Beginning at a time of significant change in my life, these episodes left me feeling disconnected from my body, and this coincided with other symptoms such as memory loss, headaches and vomiting. Upon visiting my GP, I was told I was most likely experiencing some form of dissociation as a result of anxiety. Dissociative disorders vary hugely for those that experience them, but after reading up about the condition online (something people usually do when they have hesitantly been given a diagnosis), I believed I had been experiencing periods of depersonalisation and derealisation.

The NHS website describes depersonalisation as a feeling of being outside of your body, and of experiencing your emotions and actions from a distance. I often felt as if my consciousness was floating above my body, as if I was looking down on myself from above. I was in a standoff with myself; I felt that at times I had the ability to ‘rejoin’ and yet it was almost serene to be temporarily dislocated. Something about being in that state kept me there, and I don't think I'll ever know how much control I had over that. However frightening and upsetting, it felt almost relaxing to surrender my anxiety to a detached state of nothingness. I felt guilty and confused, how could I want to receive medical help for an issue that I sometimes felt I gave in to?

Derealisation is similar to depersonalisation, but it involves the feeling that the actual world around you is unreal. Everything around me seemed distorted or animated - sometimes I felt like I was in a literal cartoon. During one episode I felt trapped inside the film Monsters Inc, which doesn't sound too scary until you imagine not being able to escape. At times I felt paranoid when near windows and doors, and sometimes saw figures or faces looking at me. On one occasion I stared blankly at someone I loved and couldn’t remember their name. It's incredibly unsettling to suddenly feel so disconnected from yourself and the world around you.

As I typically experienced memory loss alongside these episodes, it was easy to convince myself that I was making them up. As well as this, at this stage in my diagnosis the medical professionals I had discussed the episodes with seemed to all conclude that these symptoms were in some way related to my mental health. I therefore felt more inclined to worry that I was heavily exaggerating the symptoms, or that I was not doing enough to ‘counter’ these episodes. As if being mentally unwell means you have more of a responsibility to feel better- a statement I knew was wrong and yet simultaneously couldn't shake.

Collage by me

I began experiencing these episodes after moving to Uni, when I was hyper aware of how people would view me in a new social setting. I was then diagnosed with epilepsy during the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, at a time where everyone felt disconnected to their social circle. Ironically, at a time of huge medical uncertainty for so many people, the pandemic was when I began to gain some clarity and understanding in relation to my own health. It is interesting to reflect on these years of change, and see how my identity, my health and my new friendships upon moving to a new city were all so strongly interconnected.

Epilepsy diagnosis

The last thing I expected to be causing these episodes was epilepsy.

When I first visited the GP over these episodes in spring 2019 I was placed on a waiting list to be assessed by a neurologist whilst a dissociative disorder stayed as the working diagnosis. After seeing the neurologist in late 2019/early 2020, I was scheduled for neurological tests including an MRI and an EEG. These tests were to rule out the possibility of epilepsy. During the first national lockdown for Covid-19 I had moved back to my family home and whilst waiting for the results from one of my neurological tests, my brother witnessed me having my first physical seizure and called an ambulance. I immediately started anti-epileptic medication the next day after discussion with a neurologist. The seizure had a huge impact on my health, I felt physically and emotionally exhausted for weeks after the fit and my anxiety and low mood drastically worsened. At this point my health became tangible and evident for everyone to see, it was no longer that I had been experiencing ‘strange’ episodes. Instead, someone had witnessed me having a seizure and there had been an immediate medical reaction from paramedics, my GP and my neurologist.

Fast forward nearly 3 years and I've had multiple MRI’s and several appointments with neurologists, neurosurgeons and epilepsy nurses. Any medical concern relating to the brain never results in a simple diagnosis and I therefore do not wish to expand on all the details. However, the general consensus from these professionals is that I am epileptic, I have a slight brain abnormality, and that the episodes that were initially thought to be dissociative in nature were most likely epileptic, non-physical seizures.

In my opinion, I was given the impression that these episodes were purely related to my anxiety before my physical seizure took place. During my first year of university my mental health was an issue that needed to be addressed, hence I was often tearful and upset during GP appointments. As a young, visibly distressed woman, I believe that my emotional reaction during these GP visits, coupled with my gender presentation had an impact on the way in which I was diagnosed. It leaves you thinking silly thoughts like: maybe if I had cried less in those initial GP appointments they would have fast tracked my neurological tests. As if it's my responsibility to prove to a professional that my mental health symptoms do not detract from my physical health symptoms. As if maybe, my mental and physical health could have been addressed holistically - as two very important components that contribute to my general health and wellbeing. Although it is an area in need of much nuanced debate, I will briefly return to the subject of gender and diagnosis later within this piece.

I often find myself wondering how different my life would have been if I had not been re-diagnosed as epileptic.

What if my epilepsy had continued to cause my dissociative like symptoms but never any of the physical symptoms? Would I be on anti-epileptic medication or would I be on anti-anxiety medication? As a diagnosed epileptic I have been able to apply for a medical exemption from prescription charges, but someone repeatedly experiencing dissociative episodes does not have the same financial benefit.

On the other hand, this epilepsy diagnosis will have lifelong repercussions for my professional and personal life. I handed in my driving licence after my physical seizure, and it took about a year to be reinstated- if I fit again it means it will be revoked for another 9 months (plus the time it takes to get a response from the DVLA). Since graduating from University in the summer of 2021 I started a job within the Civil Service through a disability scheme. This has led to a weird form of imposter syndrome: Am I ‘disabled’ enough to apply through this? Is this fair on people with more severe disabilities?

Collage by me - Black Sail Bears

During this episode in the summer of 2019 I was hiking in the Lake District with a big group of family and friends. I remember we were leaving Black Sail Youth Hostel in the pouring rain as I began to see my surroundings distort around me. I had to stop walking and whilst my mum was helping me, my family friends danced in the rain to pass the time. It could have been a beautiful moment and instead I remember thinking I was in a circus, with bears dancing around me. The text shows excerpts from a medical letter I received a few months before my physical seizure, stating clearly that my symptoms were solely related to my mental health.

The classification of disability

It has felt bizarre to be suddenly classified as a ‘disabled’ individual, a word which feels so loaded. It also feels like an incredibly official label, with no room for doubt. The reality is that for many people the status of their health will never be as straightforward as this. Doctors have not been able to rule out the possibility that I was experiencing dissociative episodes as well as non-physical seizures, and then eventually a physical seizure. There is still, and always will be, uncertainty about what caused the onset of my symptoms. When I think back to the time period that these episodes started within, there is no way I can separate my mental and physical health. I contextualise my epilepsy as something that was dormant within my brain, and I don't believe it was coincidental that the seizures started as I began to struggle with my mental health. No doctor will ever be able to confirm this understanding, but it is how I am able to make sense of my own health.

This predicament is why a binary understanding of physical and mental health can be such an exhausting narrative for chronically unwell people to navigate through. It forces you to choose a side to identify with and to repeatedly vouch for yourself within an underfunded healthcare system. This inevitably leads to shame, guilt or general confusion.

When you're telling doctors that you're hallucinating Pixar animated characters it's not easy to stand up for yourself when a diagnosis doesn't feel quite right.

It’s why perhaps two years on, unless I am cynically joking around to my friends or family, I feel uncomfortable calling myself disabled. For a multitude of reasons I am hesitant to let go of my experiences that myself and others labelled as dissociation. But simultaneously, I also feel guilt for finding relief in the fact that I now have a physical health diagnosis. I can see how I benefit from recognition and ongoing medical support now that my diagnosis is physical, so it feels wrong to find comfort in this system.

Vicky

Vicky, a young woman in her early twenties who wishes to remain anonymous, has a similar story to mine except it is somewhat inverted. After chatting about our experiences with mental and physical health last year, we bizarrely realised how we both felt, and feel, guilt when trying to navigate between physical and mental understandings of our health. Vicky explained to me that she has a history of mental illness, struggling with severe anxiety and depression throughout school, sixth form and university. A particular issue that became apparent in sixth form was Vicky's sleeping pattern; she was struggling to get to sleep at night and would find herself exhausted during the day, sometimes falling asleep in public. Upon seeking medical professional help about this, it was suggested that she was suffering from a condition called narcolepsy.

Narcolepsy is a rare and chronic neurological condition which is characterised by the brain being unable to regulate sleeping and waking patterns normally. People with narcolepsy experience different sleep cycles, frequently entering rapid eye movement (REM) sleep more rapidly than people without narcolepsy. The resulting impact is that people with this condition can experience extreme daytime sleepiness and sleep attacks (falling asleep suddenly and without warning). These symptoms are explained more thoroughly within the link below):

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/narcolepsy/

Vicky described how being given this working diagnosis helped her to contextualise her health, it meant that she felt comfortable to discuss this diagnosis with family, friends and teachers. Vicky explained this was because she viewed narcolepsy as a ‘physical’ health condition; she now had the evidence to prove that the symptoms she was experiencing were ‘legitimate’.

Vicky then experienced a change in her medical classification; she did not reach the necessary threshold to be diagnosed with narcolepsy during a test in the autumn of 2019. Vicky explained to me that she underwent a lumbar puncture, which was used to measure the levels of a protein in her cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Her protein levels fell just outside of the threshold for her to be diagnosed with narcolepsy. For more information on this medical test please refer to the previously listed NHS website on narcolepsy, and find the section entitled ‘Measuring hypocretin (orexin) levels’ under the diagnosis tab.

Vicky was told that she no longer had a neurological condition, and was instead diagnosed with chronic sleep deprivation and dissociative episodes. Something that stuck with me during our conversation is that Vicky frequently described how she had felt ‘stupid’ after her diagnosis changed. She felt embarrassed that she had told a variety of adults about the initial diagnosis, many of whom had a professional responsibility to look after her wellbeing, only for this diagnosis to change. It is an indication that although attitudes have changed in relation to understanding mental health, there is still a reluctance for people to come forward about these issues. Ultimately, Vicky describes that the physical health diagnosis felt more legitimate, and that when that was taken away from her she felt foolish.

Binaries within binaries - gender and diagnosis

It is no wonder Vicky was made to feel this way about her health, when it is so frustratingly difficult for women and feminine-presenting people to have their symptoms taken seriously by the medical establishment. To have been initially diagnosed with a physical health condition, and then this seemingly ‘downgraded’ to a mental health condition only confirms the medical stereotypes that surround femininity. That we are hysterical, hormonal beings, more likely to make a fuss about things.

For centuries, women with unexplained health side effects and conditions have been branded as irrational. Maria Cohut puts it very well in a 2020 article, where she writes that the historical diagnosis of the alleged mental health condition ‘hysteria’ was a way for doctors to explain any female ‘behaviours or symptoms that made men… uncomfortable’. It is also well versed that the word hysteria originates from the ancient Greek word for uterus. Hippocrates and Plato believed that the womb - also referred to as ‘hystera’ - had the ability to wander around the female body, resulting in the variety of physical and mental health side effects that culminated in a diagnosis of hysteria (Cohut, 2020). For some people, health gendered assumptions add an additional divisive discourse to the mental-physical framework of diagnosis.

See Maria’s article below:

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/the-controversy-of-female-hysteria

This gender essentialist way of understanding health is of no benefit for anyone. Both men and women, as well as trans and non-binary folk, suffer from mental and physical health - as well as the symptoms which don't fit neatly into either physical or mental. Too often this debate surrounding medical bias turns into a repetitive cycle whereby the health issues that feminine-presenting people face (mental health frameworks of diagnosis overshadowing physical health frameworks of diagnosis) are trumped with the health issues that surround masculine-presenting people's health - with male suicide rates commonly stated as a counter argument. Both of these concerns are legitimate issues, but it is illogical and insensitive to compare them so as to discount the other. Let's be very clear - health inequalities benefit nobody and it is in the interest of everyone to tackle these systemic structures.

Ill health does not fit into tidy organised boxes - symptoms are never solely physical or mental, feminine or masculine. Masculine-presenting people should have access to mental health frameworks of diagnosis, and feminine-presenting people should be believed in order to gain access to physical frameworks of diagnosis.

Final thoughts

It is difficult, or indeed impossible for a large proportion of people, to not form an emotional attachment to their medical diagnosis. When the process of diagnosis ignores the complexities and nuances of chronic illness and disability, it can easily meld into our actual identity as we strive to understand our health within an increasingly overworked and underfunded health care system. This is maybe why it can feel so exhausting, and for others so affirming, when a diagnosis changes.

I have found much peace in accepting what I will never understand about my own health and instead, embracing what it means for me as an individual to feel healthy. This has meant I have disengaged with the technicalities of my ill health as much as I can. I try not to focus on the medical specifics of what was causing my episodes, and what those episodes should be classified as. It has meant acknowledging both my experiences of my mental and physical ill health, as well as everything inbetween. I am very aware that this approach is not possible or realistic for the majority of people with chronic health conditions. Although the years running up to my diagnosis were confusing, my current treatment has successfully resolved the symptoms I was experiencing- and that provided me with much needed clarity, as well as the ability to disengage with the technicalities of my diagnosis.

It takes time and energy to contextualise your own health outside of the binary logic through which it is diagnosed, but if this is an understanding that brings you peace it is an undeniably powerful approach. We may not be able to change the medical protocols which affect diagnostics itself, but we all have the ability to discuss health and diagnostics in a way which supports those who feel uncomfortable or unseen within the mental-physical binary. It’s about listening, learning and appreciating that although we may not understand ourselves - supporting someone to contextualise their own health may be the single most powerful technique people can offer to the chronically unwell or disabled.

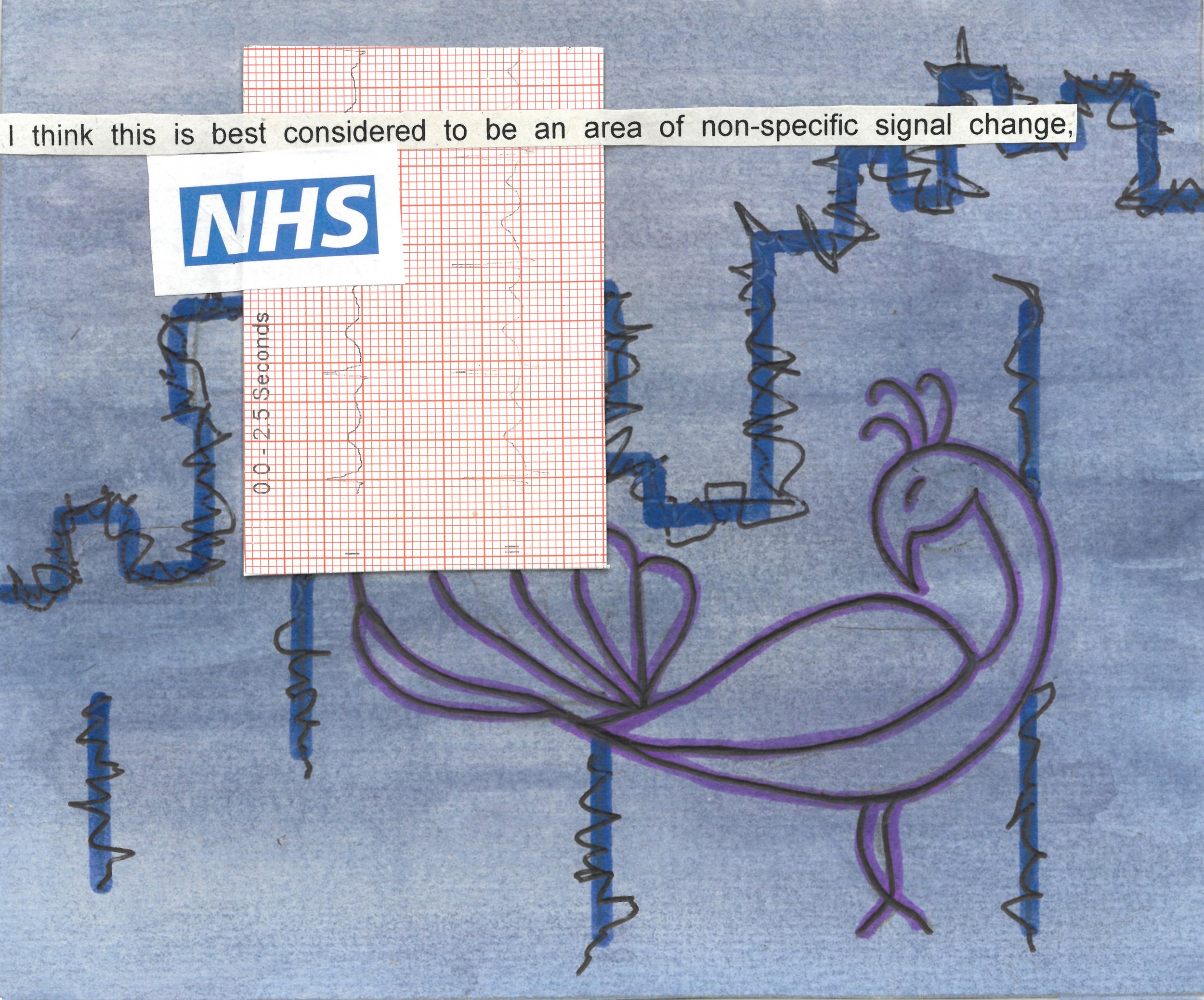

Collage by me - A Warwick Castle simulation

In the spring of 2019 I was visiting my home town of Warwick, and was showing someone I knew from Uni around Warwick castle. I remember experiencing what at the time I thought was derealisation. As the episode came on, I began to feel I was in some sort of medieval video game as we walked along the castle walls. There is a peacock garden within the castle, and I remember hearing the distorted sounds of the peacocks calling. The peacock call was so piercing it felt like a tiny bit of reality I could hold on to whilst everything else around me felt unreal.

In this collage I have used a cut out of the ECG completed by paramedics on the day of my physical seizure. The text is an excerpt from another medical letter I received post seizure, and the ambiguous language used summaries the difficulty of diagnosing a condition which did not present itself with ‘normal’ symptoms.

Thankyous and a note on context:

Much of this piece is inspired by the experiences of friends and loved ones who have all, in different ways, navigated chronic health conditions. Their pain is reflected in the way I delve into the complexities of these health concerns.

I have been extremely lucky to have had the support I needed to verbalise my experiences of health and diagnosis. Although by no means was it an easy ride, I have been provided access to NHS funded therapy and specialised neurological services (neurologists, neurosurgeons and epilepsy nurses). For me, engaging with these health services benefited me in the long term, but there are a multitude of reasons why many chronically unwell people decide to disengage with these services altogether - that's even if they are an accessible option in the first instance.

Although I have provided a summary of my experience of diagnosis and re-diagnosis, I have held back on a proportion of the specific medical details. Some of these details may have directly impacted on the tone of this piece - of frustration and disappointment. But as this whole piece strives to convey, it is possible to feel both appreciation and dismay, and everything inbetween, when accessing an intimate health service such as the NHS.